Read this ebook for free! No credit card needed, absolutely nothing to pay.

Words: 27465 in 11 pages

This is an ebook sharing website. You can read the uploaded ebooks for free here. No credit cards needed, nothing to pay. If you want to own a digital copy of the ebook, or want to read offline with your favorite ebook-reader, then you can choose to buy and download the ebook.

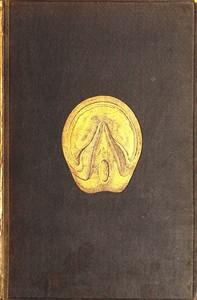

n has no equal. It can be obtained in bars of various sizes to suit any form and weight of shoe, and the old shoes made from it may be worked up over and over again.

The chief objects to be attained in any particular pattern or form of shoe are--that it be light, easily and safely retained by few nails, capable of wearing three weeks or a month, and that it afford good foot-hold to the horse. All shoes should be soundly worked and free from flaws.

The first shoes were doubtless applied solely to protect the foot from wear. The simplest arrangement would then be either a thin plate of iron covering the ground surface of the foot, or a narrow rim fixed merely round the lower border of the wall. Experience teaches that these primitive forms can be modified with advantage, and that certain patterns are specially adapted to our artificial conditions. A good workman requires no directions as to how he should work, and it is doubtful if a bad one would be benefitted by any written rules, but it should be noted that a well-made shoe may be bad for a horse's foot, whilst a very rough, badly-made one may, when properly fitted, be a useful article. To make and apply horse-shoes a man must be more than a clever worker in iron--he must be a farrier, and that necessitates a knowledge of the horse's foot and the form of shoe best adapted to its wants.

The following are about the average weights, per shoe, of horses standing 16 hands high:

Race Horses 2 to 4 ounces. Hacks and Hunters 15 to 18 " Carriage Horses 20 to 30 " Omnibus " 3 to 3-1/2 lbs. Dray " 4 to 5 "

A thick shoe raises the foot from the ground and thus removes the frog from bearing--a very decided disadvantage. It also requires the larger sizes of nails to fill up the deep nail holes, and very often renders the direction of the nail holes a matter of some difficulty.

The width of a shoe may beneficially vary. It should be widest at the toe to afford increased surface of iron where wear is greatest. It should be narrowest at the heels so as not to infringe upon the frog, nor yet to protrude greatly beyond the level of the wall. The thickness of a shoe should not vary unless, perhaps, it be reduced in the quarters. Heel and toe should be of the same thickness so as to preserve a level bearing. Excess of thickness at the toe puts a strain on the back tendons, whilst excess at the heels tends to straighten the pastern.

This form is very widely used. It consists of a narrow flat surface next the outer circumference of the shoe, about equal in width to the border of the wall, and within that, of a bevelled surface, sloped off so as to avoid any pressure on a flat sole. This "seated" surface is not positively injurious but it limits the bearing to the wall, and neglects to utilise the additional bearing surface offered by the border of the sole. If shoes were to be made all alike no shoe is so generally useful and safe as one with a foot-surface of this form, but it is evident that when the sole of the foot is concave there is nothing gained by making half the foot-surface of the shoe also concave.

There are two other forms of foot-surface on shoes. In one the surface slopes gradually from the outer to the inner edge of the shoe, like the side of a saucer. In the other the incline is reversed and runs from the inner edge downwards to the outer. This last form is not often used, and was invented with the object of spreading or widening the foot to which it was attached. The inventor seemed to think that contraction of a foot was an active condition to be overcome by force, and that expansion might be properly effected by a plan of constantly forcing apart the two sides of the foot. The usual result of wearing such a shoe is lameness, and it achieves no good which cannot be as well reached by simply letting the foot alone.

The foot-surface which inclines downwards and inwards like a saucer acts in an exactly opposite way to the other. The wall cannot rest on the outer edge of the shoe, and consequently falls within it, the effect being that at every step the horse's foot is compressed by the saucer-shaped bearing. This form of surface is frequently seen, and is at all times bad and unnecessary. Even when making a shoe for the most convex sole it is possible to leave an outer bearing surface, narrow but level, which will sustain weight without squeezing the foot.

At the heels the foot-surface of all shoes should be flat--not seated--so that a firm bearing may be obtained on the wall and the extremity of the bar. No foot is convex at the heels, therefore there is no excuse for losing any bearing surface by seating the heels of a shoe to avoid uneven pressure. Fig. 36 rather exaggerates the "unseated" portion of shoe.

The concave shoe, often described as a hunting-shoe, presents a very different ground-surface from that just referred to. It rests upon two ridges with the fullering between, and on the inner side of these the iron is suddenly sloped off. This shoe is narrow and flat on the foot-surface, and is specially formed to give a good foot-hold and to be secure on the hoof.

Free books android app tbrJar TBR JAR Read Free books online gutenberg

More posts by @FreeBooks

: In Egitto: La caccia della jena by Lessona Michele - Lessona Michele 1823-1894 Travel Egypt IT Viaggi